GCPEA News

Violence and education

The Financial Express: Education , February 7, 2015

Shahabuddin Rajon

The importance of education is indisputable. The problem is that the international community’s credibility in promising universal education has been compromised. We no longer live in the age of the nomadic pastorals. Neither do we belong to solely agrarian society any more. Education is the backbone of a nation and knowledge is power. What will happen if those backbone and power are wrecked or destroyed due to political unrest and violence?

Over the past few decades, politics-related deaths have stained the reputation of public universities in Bangladesh. As is known to all, most of the student killings had been committed by activists of student politics; but factional clashes of Chhatra League, Chhatra Dal and Jamaat-e-Islami’s student wing Islami Chhatra Shibir had also triggered violent clashes that led to student fatalities. University students have been killed in alleged political violence; very few of those cases have seen justice being delivered.

In Bangladesh, at present the BNP-led 20-party alliance’s prolonged countrywide blockade has thrown academic schedules of educational institutes across the country in disarray, for which, academic life of as many as five crore students is being hampered. The students started the New Year with high hope collecting new books on January 1 amid nationwide hartal. Still they tried to be happy skimming over the new books and hoping to do better this year. But their hope turned out to be a distant mirage as a so-called political programme put the whole education system in chokehold. Caught up in the ongoing political quagmire, students are too afraid to go to schools, breathe freely and explore knowledge with peaceful mind. They are not even safe in their school premises.

Given the state of affairs, guardians are panicked to send their children to schools and teachers are in a fix about how to maintain academic calendar. A recent report estimates that attendance in the schools and colleges of the capital has come down to below 50 per cent. School authorities are particularly in dilemma as in this situation they neither can pressure the guardians to schools nor can stop holding classes when some 40-50 percent students are present. On top of that, when around 50 percent students are absent the teachers cannot assess the preparation of a whole class.

The situation is particularly dire for about 15 lakh SSC examinees. The exam was scheduled to start on February 2, but it started only on February 6, the situation is so nerve-wrecking that the examinees are finding it extremely difficult to carry out last minute preparation. And for the students of English medium schools the situation is even worse. They already missed out an exam and lost six months because exam in this medium cannot be stopped on account of hartal or blockade as it takes place simultaneously across the world. However, a number of English medium schools in the capital have suspended classes in the last few days apparently due to the non-stop blockade and rising intensity of violence.

The kidnapping of more than 200 schoolgirls in northern Nigeria by the Islamist terrorist group Boko Haram is beyond outrageous. Sadly, it is just the latest battle in a savage war being waged against the fundamental right of all children to education. That war is global, as similarly horrifying incidents in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Somalia attest.

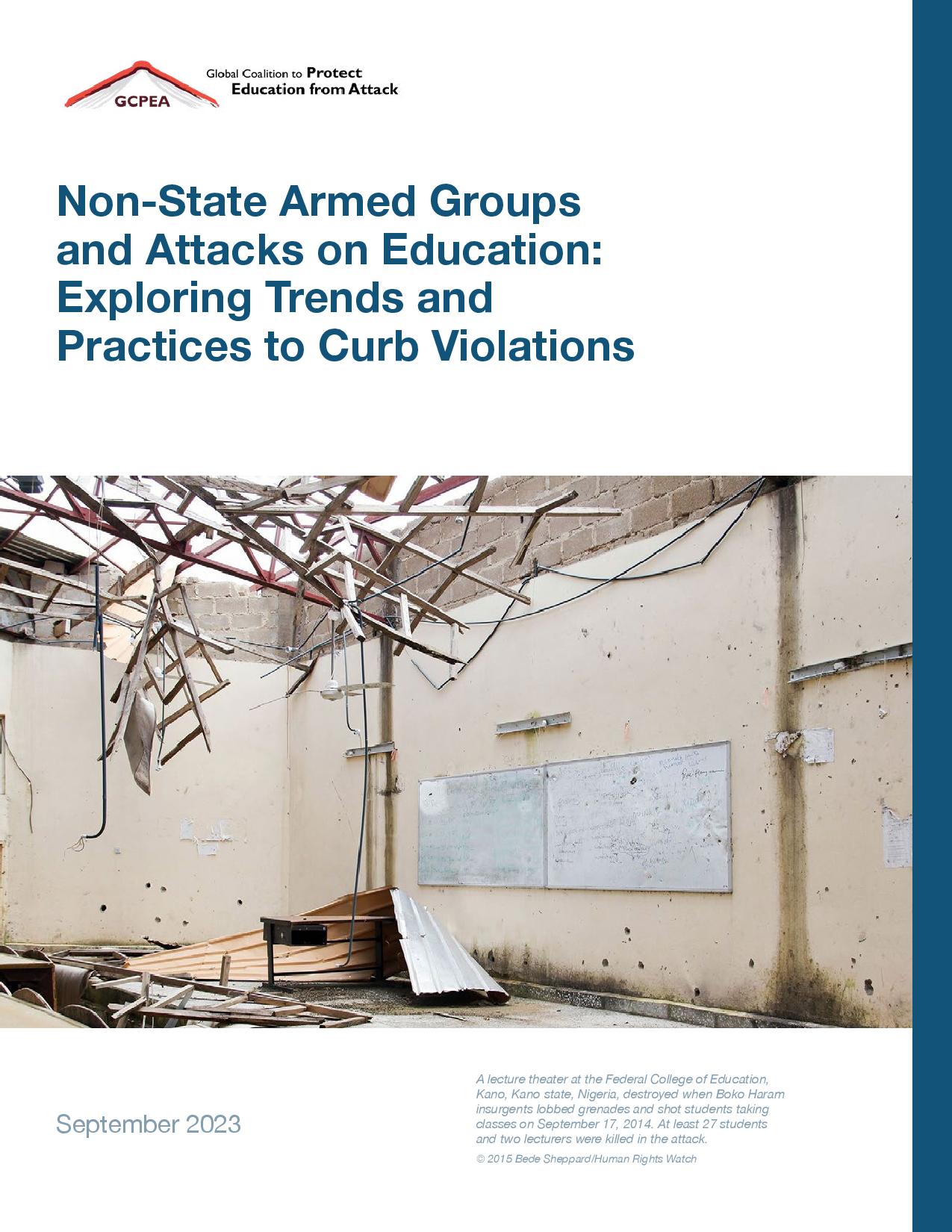

Around the world, there have been 10,000 violent attacks on schools and universities in the past four years, according to a report by the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack. The evidence is as ample as it is harrowing, from the 29 schoolboys killed by suspected Boko Haram militants in the Nigerian state of Yobe earlier this year and Somali schoolchildren forced to become soldiers to Muslim boys attacked by ethnic Burmese/Buddhist nationalists in Myanmar and schoolgirls in Afghanistan and Pakistan who have been firebombed, shot, or poisoned by the Taliban for daring to obtain education.

These are not isolated examples of children caught in the crossfire; this is what happens when classrooms become the actual targets of terrorists who see education as a threat (indeed, Boko Haram is literally translated to mean that “false” or “Western” education is “forbidden”). In at least 30 countries, there is a concerted pattern of attacks by armed groups, with Afghanistan, Colombia, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan, and Syria the worst affected.

Such attacks reveal with stark clarity that providing education is not only about blackboards, books, and curricula. Schools around the world, from North America to northern Nigeria, now need security plans to ensure the safety of their pupils and provide confidence to parents and their communities.

The experience of other countries has shown that it is crucial to engage religious leaders formally in promoting and safeguarding education. In Afghanistan, in collaboration with community shuras and protection committees, respected imams sometimes use their Friday sermons to raise awareness about the importance of education in Islam.

In Peshawar, Pakistan, in a programme supported by UNICEF, prominent Muslims leaders have spoken out about the importance of education and of sending students back to schools. In Somalia, religious leaders have gone on public radio in government-controlled areas and visited schools to advocate against the recruitment of child soldiers.

In countries such as Nepal and the Philippines, community-led negotiations have helped to improve security and take politics out of the classroom. In some communities, diverse political and ethnic groups have come together and agreed to develop “Safe School Zones.” They have written and signed codes of conduct stipulating what is and is not allowed on school grounds, in order to prevent violence, school closures, and the politicisation of education. In general, the signatory parties have kept their commitments, helping communities to keep schools open, improve the safety of children, and strengthen school administration.

The above are some of the fragment picture of education phenomenon of whole world. At present global education is passing a crucial time and definitely it is a black shadow for creating a learning society. Since education is the best way to social returns, world leaders must incorporate such norms that will ease to wipe out all black shadow and darkness on education.

In conclusion what do we expect? Millions of students remain locked out of school around the world. This not just a moral crisis; it is also a wasted economic opportunity. Providing a safe environment for learning is the most fundamental and urgent step in solving the global education crisis. Let us await to see what measures the global leaders will incorporate to mitigate this burning issue!

The writer is assistant secretary, Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BKMEA) and currently working at the Institute of Apparel Research and Technology (iART), Bangladesh,